I recently put together a workshop for making invasive species into art. Because I’m in Chicago, these were some of the invasives I have to work with here, but the biggest offenders might be different where you live. If you’re not sure what plants you’re looking at, always ask for help from apps like Seek or iNaturalist and from experts. One of the biggest signals that you are amongst invasive plants is if they are the only thing you can see.

Making Invasive Species Into Art

Many people used to believe that the Earth was the center of the universe. Then many of us thought that our planet was AT LEAST the center of the solar system. The more we learn about the cosmos, the less big we become.

Ernst Haeckel, who coined the term “ecology” and merged art with science in his famous intricate drawings of organisms, saw himself as Darwin’s biggest defender on mainland Europe. He also argued that the pinnacle of evolution was not only human beings, but the German man. So you could see where that line of logic could lead one. The world to many Europeans was theirs by right, ruled from man’s position at the top of the tree of life.

But as more data came in and the losses mounted, it became clearer and clearer that instead of being the ones for whom the planet was created, humans were actually the single biggest biotic threat that Earth has ever known.

One of our many means of destruction has been the transport of species all over the place, far from the ecosystems that they evolved in. The vast majority of those nonnative species are actually benign. But some species, when taken out of their home ecosystem where they’ve developed over millennia, find new habitats much easier to flourish in. The natural checks on their populations are removed and they begin to take over their new habitats, hastening local extirpations, putting undue pressure on conservative biota. Given this behavior, many in the conservation world will point out that humans are the original and most effective invasive species. The only universe that we are the true center of is the universe of bullying, colonizing, invading. We are the best worst, the thinking goes.

However, unlike other invasive species, we can make choices about our impact on and behavior within our ecosystems. We don’t have to behave like colonizers (indeed many indigenous people might take exception to being called an invasive species). We can participate in the community of our nonhuman neighbors. We can share. We can build. We can restore and protect and celebrate. There doesn’t have to be a center of everything. In fact, humans aren’t even the only creature that can make sustainable choices: anteaters, for example, will make sure to visit many different ant colonies for their food sources rather than just decimating the first one they find and eating their daily ant quota.

When there was less of us, and our impacts were lighter, humans have repurposed organisms into remarkable things. Agricultural variety, plant and animal domestication, textiles, building materials, paints and dyes, paper, medicines, basically everything you can get at Target today has its roots in things harvested and manipulated from the natural world.

Now that there are more of us, it doesn’t make sense ethically or practically to have all of our stuff be taken straight out of nature. Most of us are not hunter/gatherers, so any hobbyism we pursue like foraging, woodworking, dyeing, paper making, etc... should not put any strain on our local natural spaces. We have to choose sustainability and noninvasive behavior. Therefore, turning to invasive species for our craftwork can serve the function of reintroducing ourselves to our cultural practices of creating things from natural sources, while not hurting our ecosystems. In fact, familiarizing ourselves to the most prolific local invaders and how best to remove each one actually benefits nearby biodiversity health.

Here are some suggestions for what you can create out of invasive species, but there’s a lot more to discover than this list. Be inspired!

Food

Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) was brought here as a garden plant and can be one of several weedy species that you can forage instead of, say, ramps; a tasty native plant in the onion family that can be sustainably harvested, but is often illegally poached from forest preserves. See also my recommendations for foraging below.

The most common use for it that I’ve encountered is as the main ingredient in pesto sauce. Here’s a recipe from farmsteady.com:

Ingredients

2 cups garlic mustard leaves

1/4 cup walnuts

2 cloves garlic

1/2 cup olive oil

1/2 cup pecorino, grated

Directions

In a food processor, combine garlic mustard leaves, walnuts and garlic and pulse until very finely minced.

With the processor running, slowly pour in the olive oil and blend until smooth.

Add the cheese and pulse to combine.

Paper

Common reed (Phragmites australis) can not only take over our native wetlands, making it impossible to look past the millions of feather duster seed heads and actually see any open water, but it can actually outcompete itself until a stand of them is just a clone of a single individual. And like many fibrous plants, it can be made into paper, see the process from May Babcock here:

1. Cut stalks up and soaked overnight in water.

I cut up a lot more than I needed.

2. Boiled with a caustic solution & water.

I used soda ash from a ceramic supply company, but you can also order washing soda as well, to removes lignins and other material from the cellulose fiber, making your paper stronger and archival.

I used a stainless steel pot that won’t be used again for food. The stainless steel is nonreactive.

3. Rinse, Rinse, Rinse

I rinsed the fiber well, to rid it of any caustic solution. The water should run clear.

4. Beat into a pulp with a Hollander Beater.

I used my Critter Beater, a portable beater built by Mark Lander in New Zealand. A Hollander beater macerates, cuts, and fibrillates the fibers into a pulp with water.

5. Made the paper

See my educational blog Paperslurry for photos of how to pull sheets of paper from a vat of pulp with a mould and deckle.

I would like to one day take it a step further and make it into seed paper, imbuing the phragmites paper with native plant seeds so that you can write poems on the paper and plant them. Which is pretty witchy.

Dyes

Many plants can be used in different ways to make natural dyes. Japanese barberry, wineberry, and oriental bittersweet (pictured above) are all invasives that can be used to make various dyes for application to fabric or wood. Often the wood needs to be soaked in soy milk or some other substance to make the dye set in deeper, and the plant material you are using often needs to be heated (probably in a non-food pot) and mixed with some kind of mordant (like citric acid).

Look at this snake and bracelet I made with natural dyes.

Woodcraft

Woody invasives like common buckthorn and amur honeysuckle can be used to replace all manner of wood-based projects from small to large scale sculpture, to garden fencing, pavers for walking upon, as well as firewood, coasters, a simple bludgeon. Whatevs!

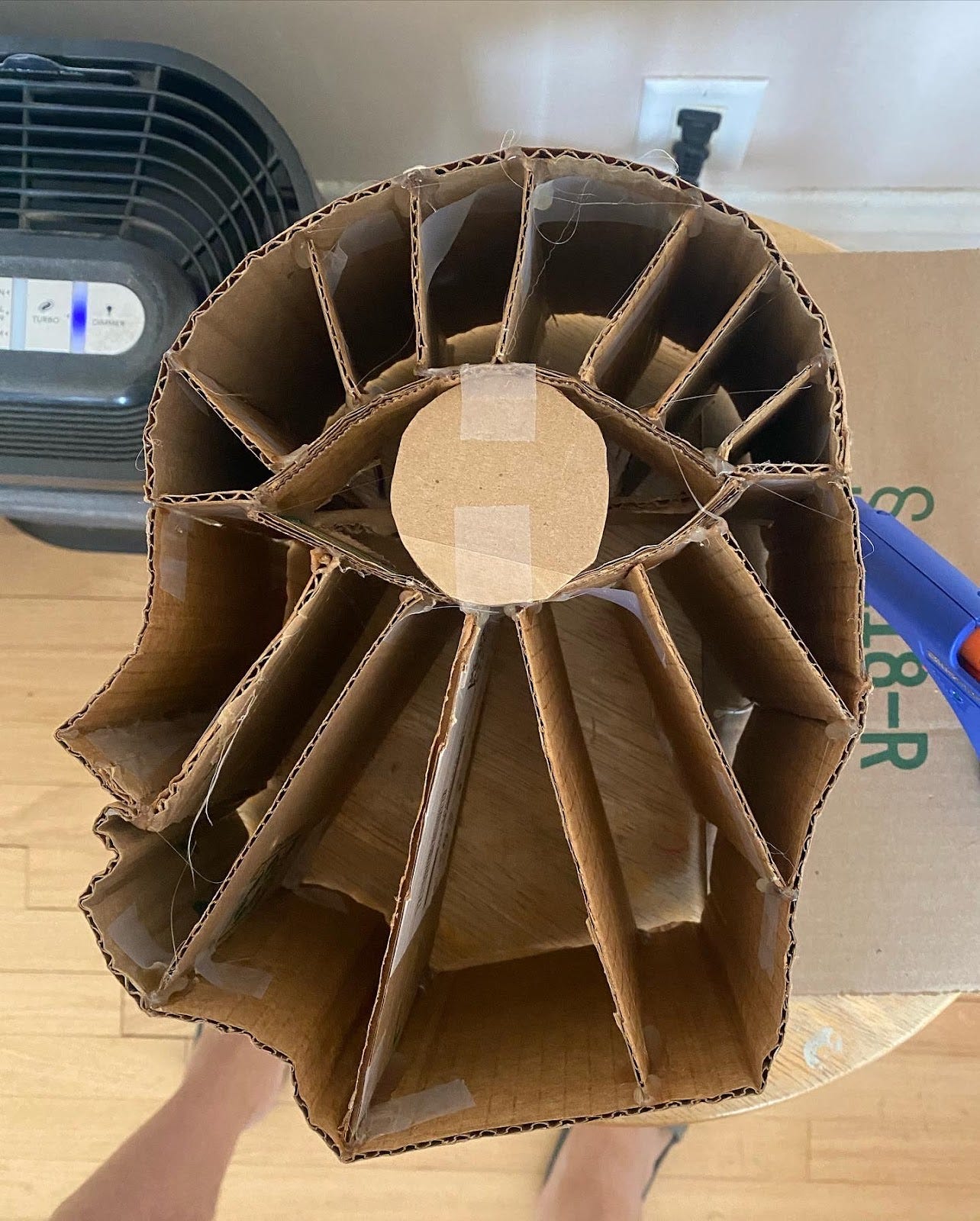

Here’s my process for imitating one of Olga Ziemska’s Of The Earth sculptures on display at The Morton Arboretum.

A note about wild foraging

Foraging can be a deeply enjoyable experience - there are many plants, animals, and fungi that have a history of human use, especially by indigenous people around the world. But unlike domesticated species, foraged species often rely on ecological factors in order to become useful to us. Some of those factors might include processes already disturbed by modern human practices, so any additional strain to wild populations could have unintended effects beyond just your fanciful browsing.

Like many side effects of colonization, there are indigenous American practices that get lost when non-indigenous people attempt to simply take what they like from traditional ecological knowledge and discard or ignore anything that doesn’t give near instant gratification. The concept of the Honorable Harvest, as outlined in books like Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, looks to ways of taking from nature that don’t deplete local populations for short term human pleasure. A simple principle of the Honorable Harvest, according to Kimmerer, is to never take the first of something you find, and never take the last. Another way it was explained to me on a neighborhood tour of native plants from the American Indian Center in Albany Park, Chicago, was that for every one plant or part of a plant that you take from nature, leave another for animals to eat, and another for the plant to make more of itself. If we have to take something from nature, 33.33333% is the most of anything we should consume.

But beyond that, especially in relation to foraging for invasives (which in many cases you can take 100% of, if you have the gumption!) it’s worth asking whether you need to forage something, even if it is honorable and just a third of the population you encounter. If you are food insecure, that makes sense. If you are an indigenous person, and it is part of your cultural practice, that makes sense. If you are a foodie who loves ramps and wants a wild supply of them for your restaurant, it doesn’t make sense.

My general rule, as a food secure white guy, is to only take things that I have absolute certainty that my taking will have no impact on the health of the ecosystem (and also I need landowner permission). It’s also a good rule when you’re not sure if something may give you food poisoning without proper preparation. Leaving things alone that aren’t monitored by the FDA has a 100% survival rate.

Good luck out there!

And here’re a few of the things produced in my Turning Invasive Species into Art class that I taught at The Morton Arboretum on 8.26.23.