This is a new thing I’m doing in this newsletter. The way it works is I review a book written by someone I am lucky to know personally and am unapologetically invested in their success as humans. So you can either take any praise I heap onto their works with a grain of salt or just accept the fact that loving someone can only enhance the reading experience.

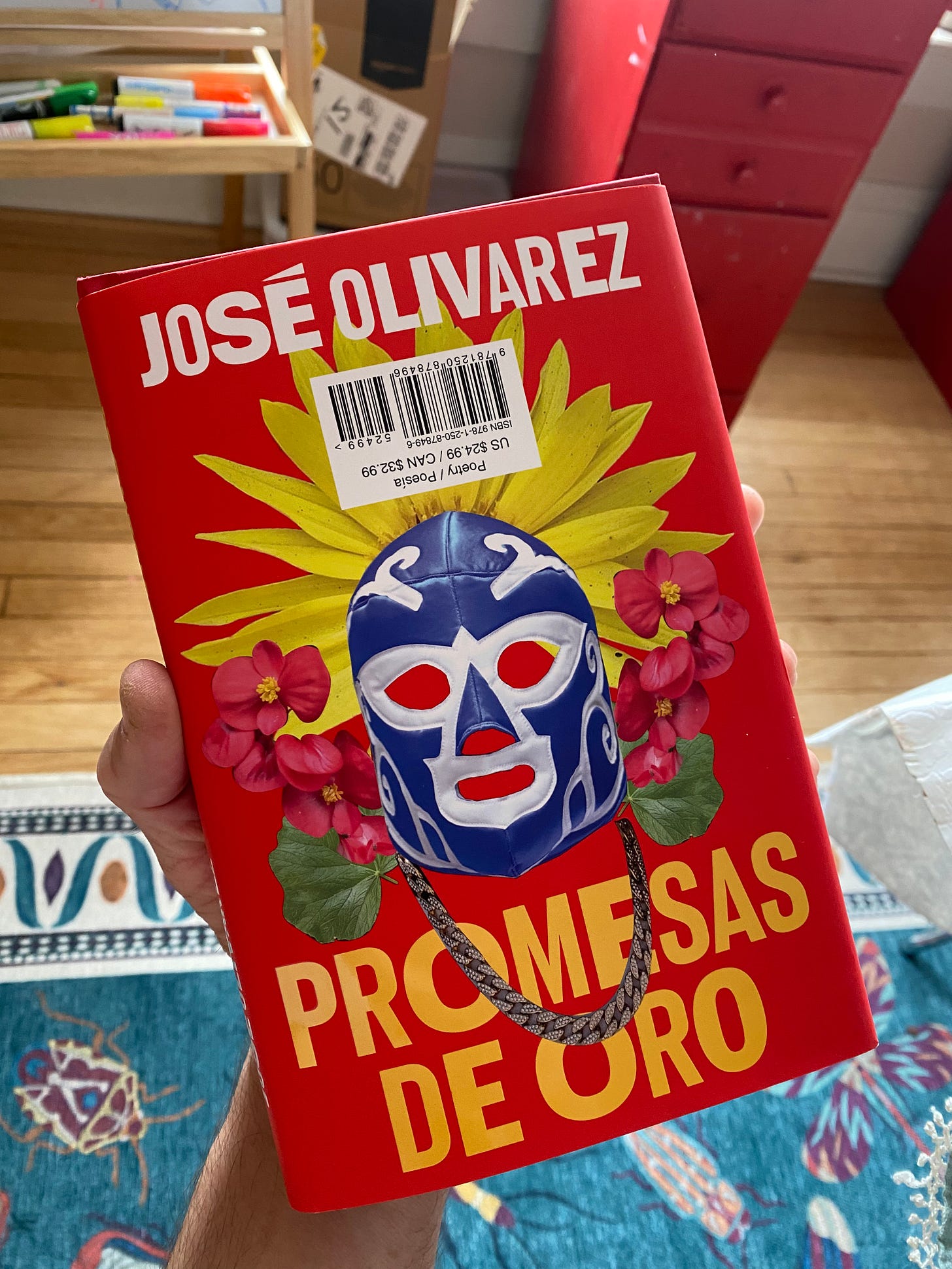

Lucky to be one of the ~2 billion people in the world who speak English or Spanish because José Olivarez has a new book called Promises of Gold/Promesas de Oro. Written in English by Olivarez and translated into Spanish by poet David Ruano González, one need only to LITERALLY flip the script to change which language you read in.

Magic!

And even though I had to pay money to own this book, the gold it promises is the soul kind. So it’s a net gain for me!

Olivarez explores his (sometimes conflicting) identities as son, brother, Mexican American, Chicago ex-pat, and partner. He interrogates his (sometimes conflicting) roles in capitalism, art, friendship, masculinity, body image, and in his big big feelings.

The clashing and smooshing together of his various selves drives the tension in many of these poems. Take for instance “Nate Calls Me Soft” where, after remembering driving with his friend Nate to open mics, he says:

if i confess that the memory alone

makes the corner of my eye itch,

would you call me soft? Nate says yes.

Bee says duh. Adam says you were

the softest. My therapist says, let’s talk

about your parents. My brothers

say, if all you’re gonna do is talk,

then pass the blunt. Mexican Jesús

says nothing.

Here he is holding up his emotional sensitivity to his various identity mirrors (friends/poets, therapist, brothers, Mexican Jesús, etc…) and they all reflect different things back to him. And despite these different mirror-imaged-selves, it doesn’t feel to me like he’s too worried about being soft. Maybe he used to be hung up on it, but here he has affection for his softness, and his friends do too. He ends the poem with:

…tonight,

the stars are hidden by the brash lights

of the city & i want to say my friends

can see my softness through all the jokes

i crack, but maybe i don’t need the stars

to be tender. maybe the next time i see you,

i’ll slap away the dap, pull you in close,

& tell you under the ordinary streetlights

how much i love you.& that you still ain’t shit.

It’s not a secret that Olivarez loves his friend Nate Marshall (who is almost certainly the Nate in this poem). They have been friends since like, I don’t know, 2005? But it’s not just about witnessing these two be all cute with each other - this poem can open up permission or give a set of instructions for growing comfortable being vulnerable with your friends (if that’s something the reader might be searching for). Or, for people like me, it validates the love I have for my friends that I gave up hiding a while ago.

His poem “Poetry Is Not Therapy” starts:

but that doesn’t mean i didn’t try it

god knows in those moments

when it felt like my gut was being wrung

like a wet rag, i wrote bad poem

after bad poem. who cares? healing

wasn’t the point. (healing is a capitalist pursuit)

Here Olivarez navigates the limits of poetry’s capacity to heal or make sense of tragedy. Often poetry is celebrated for its magical properties - how it can imagine a better world, bring impossible things together, give shape and words to new and old feelings. But it’s precisely this kind of magic that can seduce us into thinking we are doing real work (on ourselves, for our community, against injustice, etc…) when what might be happening is just axe-wound bandaids. Sometimes we just need the help of a professional.

Of course, paradoxically, Olivarez IS a professional we can employ to help with the things we need poets for. Take for instance “Poem with Corpse Flowers & No Corpses.” (I’m just gonna type the whole thing so it can live in my fingertips!):

Hundreds line up for blooming “corpse flower”

at abandoned East Bay gas station.

—The Mercury News, May 20, 2021begin with the mourning breath of the corpse

flower. consider what rots might feed the veins.

alternatively: all vanity requires stink.

on the other end of the best steak of your life

is a cow moaning a song of agony.

somewhere there is a producer flipping that cow’s

last word into something that can hold a snare drum.

one of the first questions our ancestors had to answer

was what to do with the ones who die.

at some point, they started feeding the dead

back to the ground & naming babies after them.

so when a corpse flower opens up

in an Alameda gas station it’s a minor miracle:

not a Warriors game, or a funeral, or a wedding,

but the whole block gathered to watch a flower

remind us of our family—not dead

& not gone—ready to bloom again.

It’s a shame that in this country it often takes a remarkable event like a rare, stinky flower blooming for a community to have permission to gather and be collectively awed. Even before lockdowns and the poisoned breath of our neighbors, many of us have no incentive to be near people whose only similarity to us is a shared zip code. But when it does happen, it can be, yes, healing: healing a wound you didn’t notice growing. A minor miracle.

Reader, I posit here that this poem is also the minor miracle it sings. The book. José. Miracles. And the great thing about minor miracles is that they happen all the time, can be purchased for $24.99 in the US or $32.99 in Canada and can be accessed whenever you are ready for one, when you open up to their possibility, when you could really use one.