This is the second installment of the series Conflict of Interest, wherein I review books written by people I love IRL and whose work I love IMRH (in my real heart). I will not pretend to want anything but wild commercial success for these people, even if capitalism is a scourge upon the world. Oh! Speaking of the world…

You, average American, might be thinking, “Huh. I sure am hearing a lot about the apocalypse these days,” what with the climate crisis and all. Peel back that and behind are plenty of other apocalypses. Mobilizing nuclear weapons; a global pandemic whose deadliness is magnified by the politicization of public health; the greatest legacy of the Anthropocene is the planet’s first mass extinction caused by a single species; not to mention you and everyone you love will die. Fun stuff!

But then in 2001 you might have thought, “Huh. I sure am hearing a lot about the apocalypse these days.”

And maybe in 1968 you might have thought, “Huh. I sure am hearing a lot about the apocalypse these days.”

Or maybe 1941. 1918. 1861. 1775.

And probably, if you are not a white American, you might have been hearing a lot about the apocalypse off and on between now and 1492.

The world has been ending a lot for a long time. And for countless people and other organisms, the world has already ended. When destruction comes for your world, sometimes you’ll survive. Most of the time you won’t.

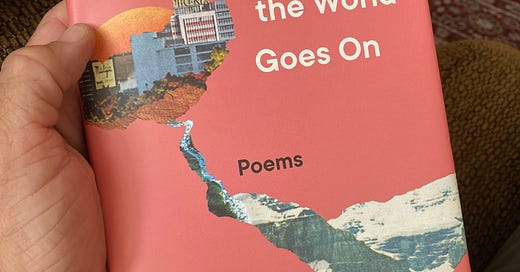

Franny “Frances” Choi dives headfirst into many of these apocalypses (and many many more!) in their third poetry collection, ambiguously titled The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On. Jk, the title is exactly what this book is about, oscillating rapidly between these two clauses as its dialectical vehicle. In one of the poems titled “Upon Learning That Some Korean War Refugees Used Partially Detonated Napalm Canisters As Cooking Fuel” Choi says:

Dystopia is the word for what’s already happened

so many times, it’s the reason _________’s so cheap.

Which is a much shorter way to say everything I just said.

And if you were hoping for the “World Goes On” part to alleviate your apocalypse-angst, you better go ahead and let that world end as well. This is not a pop-psychology book about how to conquer your existential dread. But it isn’t just “Armageddon Porn1”: Choi's poems allow us to look at some of the worst things that have/will ever happen intellectually and emotionally distinct from nonfiction on the topic(s). By creating soft, precise music around these horrible images it allows us (maybe just me, I don't want to speak for you) to look at them long enough to reflect more deeply. When people are talking about the real bad shit going on everywhere, all the time, my instinct is to look away, put my fingers in my ears, and go "blahblableebloobleeblahbluh." But all that response does is makes me carry the fear of merely looking at and contemplating annihilation into a ubiquitous, low-level panic. Or as Choi says in their poem "September 2001": "I was so afraid/of seeing dead people that I saw them everywhere."

Look it’s heavy stuff, but I really like this book! And so does my dog. See:

And they do offer relief from the relentless world endings, the way you might find yourself enjoying playing ridiculous games with your daughter while your own father is dying in a hospital, hypothetically2. Or the relief is more practical. In a different poem also entitled “Upon Learning That Some Korean War Refugees Used Partially Detonated Napalm Canisters As Cooking Fuel,” Choi says:

All night, doom rang from the sky. And in the morning,

there are mouths to feed…

The poem concludes:

Every day of my life has been something other than my last.

Every day, an extinction misfires, and I put it to work.

Choi bringing themselves into this poem, stating that they too make pragmatic use out of destructive forces, isn’t an anomaly. Snippets of their inner life and biography are inextricably entangled with the various doomsdays du jour in each poem. Much they way we all experience (social, environmental, political, local, personal, etc…) tragedies, unable to remove our perception of them from our own thoughts, histories, feelings, and daily routines.

When I got about 3/4s of the way through the collection, I could feel my capacity for sitting with catastrophes beginning to fill up. I remember thinking, “Maybe I can just write the review based on what I’ve read so far.” But then lo! A turn!

A longer piece called “How To Let Go of the World” get its title, Choi explains, from a documentary about climate change of the same name. The documentary leads their friend sam3 to ask "Should I jump off a building." Literally letting go of the world, which is what it feels like the whole book is asking us to consider as well: with so much relentless injustice and trauma, should we let go of this world and retreat into distraction or death? Choi concludes the piece with:

In lieu of proximity to firefighters; in lieu of the ability to speak the airless language of ghosts; or to reverse the logic of molecules; or to force Exxon to call the hurricane by its rightful name4; or to convince my friends not to launch themselves from the rooftops of every false promise made by every rotten idol; in lieu of all I can't do or undo; I hold. The faces of the trees in my hands. I miss them. And miss and miss them. Until I fly out of grief's arms, and the sky. Catches me in its thousand orange hands. It catches me, and I stay there. Suspended against the unrelenting orange. I stay there splayed, and dying. And shocking the siren sky.

All Choi can do in the face of all this bad is to exert the entire energy of their life against the overwhelming call to despair, to burst as lightning and dissipate their indestructible energies into the air around them. We will die. But we can push ourselves against the seduction of nihilism to the benefit of all those who we are bound to - our loves, our groups, our species, our world. Or as they say later in the poem “Coalitional Cento”:

am I the colonization or the reparations?

I, too, make the decision. I carry it with me

connect the dots in our real lives

ginger roots cross mountains

we will not live quietly

I choose to be the reparations

The argument of the book against resignation—despite—to imagine worlds we do not (yet) occupy, to not live quietly, to be lightning, to choose to be reparations, for Choi, this is the only choice. You can see part of the word “PHOENIX” on the cover.

For the last two years, me and a lot of conservationists in Illinois have been trying to save Bell Bowl Prairie, a super rare, super biodiverse grassland unfortunately living between the two runways of the Chicago Rockford International Airport. The airport wanted to build a road through the prairie, leaving just 6.2 acres of it left, and we tried everything we could think of. We sent politicians thousands of letters, made thousands more phone calls, sent thousands more emails and social media posts, devoured the intricate bureaucracies that oversee a project like this, we organized rallies, made beautiful art, wrote op-eds, circulated a petition with 100,000+ signatures, had hundreds of news articles written about it, spoke at city and airport board meetings, and despite all that, they bulldozed the prairie. As soon as they could. There is only about 2100 acres of original Illinois prairie left in the entire state. They didn’t have to build the road through it. We all cried for the lost soil—its structure and its makeup, microscopic fungi, bacteria, seed banks, and sleeping invertebrates. We cried for this invisible carnage.5

So we were all pretty upset about. A week ago we had a memorial service for the prairie. People spoke about what was lost, why they care, what we learned, what we can do next. I led a poetry workshop where we wrote poems on seed paper with prairie seeds inside that could planted later. In the workshop, I read Franny Choi’s “Wildlife.” A poem towards the end of the book, it starts with a quote from a news anchor who accidentally says, “a massive wildlife—uh, wildfire—exploded to ten times its previous size.” The poem then imagines what a massive wildlife explosion would look like as plants and animals around the world come back to life, come back to healthy homes. Oil is converted back into living organic matter; whales clog the sky. It’s a celebration, albeit hypothetical and impossible. More tears.

In another workshop I once taught (I promise this is going somewhere), I asked some 7th graders to make a list of things society thinks are ugly and then pick one to write a poem where they were try to make that thing beautiful. A student raised their hand and said, “How do you make racism beautiful?” And I was trying to think of a good answer, and was about to say, “Uh, pick something else,” but then another student raised his hand and said, “Well, it’s not that racism is beautiful, but the people who come together to fight it, those people are beautiful.” Weep weep weep.

I say all of that to say, all of the people who come together to fight racism ARE beautiful. All the people who come together to save a doomed prairie are beautiful. All the people who look directly into the face of massive destruction and choose to fight it anyway are beautiful. And those people, the work they’ve done and will do, the exploding ecosystems of their relentless care, they thread the world like mycelium, holding it all together, invisibly distributing the best of us outward.

The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On is the best possible answer to the question, “Well, who gives a shit?”

I will be trademarking this expression as soon as I figure out how to do that.

At my dad's memorial service, my five-year-old motioned for me to lean down so she could whisper something to me. She said, “I’m married to Rozzy [her cousin] but she just told me she wants to break up with me and I’m DEVASTATED.” and she squealed and ran away.

Earlier in the poem, Choi says that Exxon IS the rightful name of a hurricane.

My faith can’t be seen with the naked eye, but you can see it with a microscope.