I’m not the first person to look at the sinister maw of the capitalist death machine as it eats the children of the world and think, “Hmm, sure doesn’t seem like poetry can help much here.” Truly, in many ways, it can’t.

If you ask a poem to do a lot of things, it’s gonna disappoint you. Poetry cannot paint your deck for you. Poetry cannot file your taxes for you. Poetry cannot call your congressperson for you. It can’t stop or reverse murder, it can’t store carbon, it can’t home endangered species. If you print it out, you can at least make it into an airplane or use it to stabilize a wobbly table.

So what good is it?

There’s a video that shows up in my IG sometimes of Ethan Hawke answering this question in a very Ethan Hawkey way. His general idea is that poetry helps us make sense of feelings that might be too overwhelming on their own. In that way, poetry (art) becomes a Rosetta stone for our humanness and helps us connect with other’s humannesses across time. That’s cool.

I think it can also be a rhetorical tool - helping convince people of things (for better or worse). I can’t speak to its efficacy, but I can see a world where the abstraction of language combined with the aesthetic choices of poetry allows a reader to sit with something that, when viewed straight on via photography or video or talking head, is just too overwhelming.1

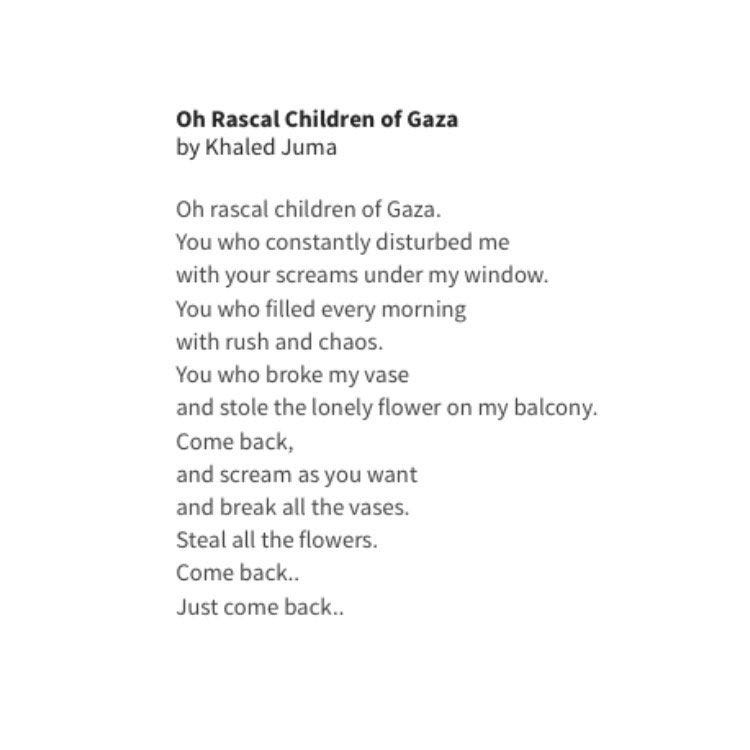

For example, take this poem by Khaled Juma that has been shared a lot recently:

Let us impossibly pretend this poem exists outside of a very specific history. The narrator seems to be grappling with the loss of children in his community and negotiating (with them?) to return. For him, it would seem that property and quiet are not equal trades for human life. Taken impossibly out of specific history, such negotiations might seem obvious. Of course we would rather have rascal children rather than no children.

But the poem doesn’t live outside of a specific history and it’s not being shared around right now because a bunch of people just happened to want to defend the right for children to exist. The children in this poem are Gazan, a place where the median age is 18. And it’s not just a coincidence that Gazan children are half the population there - so many of the grown-ups have been killed and jailed for decades.

In the poem, the rascal children of Gaza are gone - why?

Or take the following two poems by Palestinian Maya Abu Al-Hayyat (translated by Fady Joudah) from her recent collection You Can Be the Last Leaf.

You Can’t

They will fall in the end,

those who say you can’t.

It’ll be age or boredom that overtakes them,

or lack of imagination.

Sooner or later, all leaves fall to the ground.

You can be the last leaf.

You can convince the universe

that you pose no threat

to the tree’s life.

What does the universe think about the leaf who the other leaves say threaten the tree’s life? What even is the universe here? What is the tree? Who are the leaves? Does simply knowing the author is Palestinian change your reading? As someone witnessing the discourse around the current conflict, does this hit you differently than it might have two months ago?

Speaking of children:

Children

A child’s hand sticks out of the rubble

and sends me counting

my three children’s limbs,

their digits, examining their teeth

and eyebrows.The silenced voices in Yarmouk

turn the volume up on my radio, TV,

and drown the songs on my laptop.

I pinch my kids in their love handles:

let there be crying,

let there be noise.And the hungry hearts

at Qalandia Checkpoint open my mouth:

I crave salt for my emotional eating

to feed weeping

eyes everywhere.

Where is the author in the first stanza? Why do silenced voices turn up her radio and TV volume and drown out the music she plays? Like the Juma poem, why does she welcome the noise of children? Does the line break between “weeping” and “eyes” change the reading for you at all?

Maybe for you, all poems right now are laptop music and the stories coming out of the world’s conflicts are too loud to ignore long enough to engage with art of any kind. That seems to me to be a fine reaction. But possibly you are having a hard time sifting through all the opposing rhetoric of the various parties and you need help establishing where you stand. Possibly, these, and other poems, can help you to find your positions on the matter, and in a way that is self-constructed and not given to you by someone in charge.

Or you feel mad (angry and/or nuts) knowing exactly where you stand on the matter and seeing so many people (some of them friends or allies in other struggles) adopting a stance on these conflicts that seems to be pro-child murder. It could be poems like these that help you feel connected to the reality you thought you shared with people. As sad or difficult as these and other poems can be, they might be able to help ground us in a place we know is true. This, in turn, might give us strength and conviction to face the madness again and convince it that the leaves pose no threat to the life of the tree. The leaves grab light for the tree and turn it into food. The leaves take the ungrabbable sky and transform it into solid wood. The leaves are miracles and without them, the rest of tree, eventually, dies.

Maybe you don’t get there without poetry. Maybe that’s the good it can do.

Not sure this applies to sociopaths.